Why mission government failed

And what comes next

Author’s note:

Welcome to Re:Think. And for many of you, welcome back!

We decided to move our blog and newsletter to Substack.

Re:State is a cross-party think tank, based in Westminster. If this is the first time you’ve come across us, please subscribe to keep up to date.

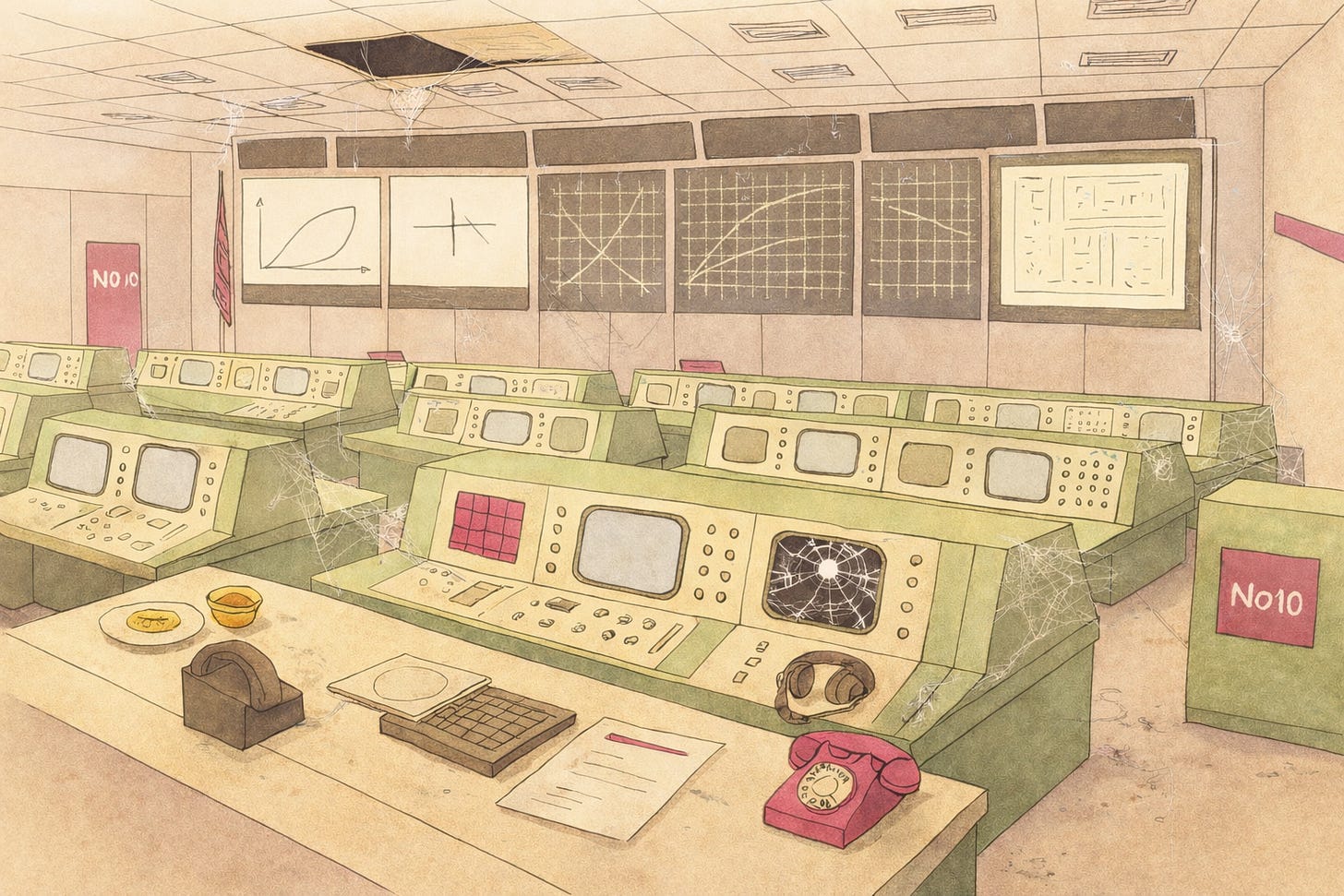

Why did the Government’s idea of governing through “missions” vanish without a trace? In our wrap up of 2025, we said the concept of “mission-led government” was the casualty of the year:

“The delivery philosophy the Government entered office with didn’t survive contact with the State they found themselves leading… its sudden absence from all government communications makes it hard to see a future where it’s anything more than a list of things the Government would like to do. Not with a bang but with a whimper…”

The responsibility for writing the obituary on mission-led government will ultimately fall to the historians. But policymakers don’t have time to wait until the dust has settled before asking the important questions about its failure.

Why did a Government with such a specific theory of change, and so much time in Opposition to prepare, abandon their plan within a year of taking power? Was it a lack of imagination, or execution? Is it just a failure of these missions, or the theory of missions in general? Is it encouraging the right introspection among policy thinkers about why it failed, including the many (including Re:State) who wrote about how to make a success of mission-led government back in 2024? What will replace it – and more important, what should replace it?

The missions aren’t working

The missions the Government set out in their manifesto (and then again in a speech in December 2024) aren’t going well.

Some are seeing progress, but at a snail’s pace. Elective care backlogs are down, but the wait lists still stand at 7.3 million, with 62 per cent receiving treatment within 18 weeks against a target of 92 per cent.

Others are looking impossible. New housebuilding stats show that completed homes are down compared to the year before – closer to 200,000 a year compared to the 300,000 a year the Government need to meet their target of 1.5 million more.

These aren’t missions which were set up to succeed. In our paper ‘Mission control’, we recommended governments set specific and credible missions.

Although many of the missions are now specific and measurable, in opposition the list Labour used were not – they were much vaguer. It took the first six months of governing to define and agree what the actual objectives would be, meaning they lost the initiative and are now scrambling to catch up.

Most of their targets are not credible, but some are too credible. Take their growth mission, for example. The Government could easily hit the mission objective and miss the point, because they’ve set the bar so low. The economy is growing (but even more slowly than it was before the election), and household disposable income is growing at the same sclerotic pace. Ministers may meet their target of improving living standards compared to when they came into office, but only barely, and what’s the point if the public don’t notice change?

The most popular explanation for failure in Whitehall is bad governance – that the Prime Minister didn’t chair the Mission Boards the Government set up, leaving that to other Ministers to lead day-to-day. This criticism has roots in the ‘deliverology’ approach of Michael Barber and other practices from Labour’s last stint in office. Maybe that’s part of the story – after all, New Labour delivered impressive public service reforms in part through the personal focus that Tony Blair brought to areas like the health service and asylum backlogs.

But Blair’s government didn’t just rely on the PM’s time and energy – they also brought in a lot of outside expertise and put experts in charge of delivering their priorities. Instead of copying that playbook, most of the Government’s missions are led by civil servants alongside their day job.

There are too many missions

The biggest implementation challenge of missions has been focus. The Government has picked too many. The five core missions together cover the work of all the biggest government departments, and over 80 per cent of public budgets – hardly a way of focusing down on their top, top priorities.

When you combine these missions with other big, urgent priorities that didn’t get the same label, there’s barely any capacity to do any of them well.

With peace in Ukraine still seeming distant, and our biggest ally the United States becoming increasingly temperamental and unreliable, defence of the realm is increasingly the Government’s top priority – an expensive and challenging one to improve alongside delivering their core missions. The same can be said of immigration – consistently a top priority of voters, and a huge focus of ministerial energy since they took office.

When everything is a mission, nothing is a mission. Without deprioritising some things, it’s hard to focus on others. When there are too many missions, every policy can be claimed to play a role, and nothing can be deprioritised. Ahead of last year’s Spending Review, Ministers were even accused of ‘mission washing’ areas of their budgets to prevent them being cut or reallocated to other areas – hardly disciplined prioritisation.

It’s telling that the only “mission” the government are still talking about is growth. In the long-run, a growing economy is the only thing that can pay for all the other priorities the State has. When the growth rate is close to zero, then everything becomes zero-sum – for one group to get more from the State, other groups must lose out. If they can get the economy growing at the same rate as other G7 countries have seen since the financial crisis, then there’s a chance they can deliver other big goals.

But in the short-term, prioritising growth is a trade-off too. It requires political capital to put the economy ahead of other priorities and to take on the vested interests who stand to lose out from growth. There’s little sign of that commitment from a Government which already watered down their Planning and Infrastructure Bill, pursued damaging legislation on renters and employment rights which will constrain the supply of good jobs and homes, and has raised taxes on business and investment.

The theory is flawed

But even if some missions succeed, the big idea of missions as an operating model for government looks set to fail.

Because mission-led government meant a lot of things to a lot of people, and the intellectual foundations were much broader than just a belief that governments should pursue big, audacious goals – ‘deliverology’ was far from the only component.

The concept drew on inspiration from big strategic shifts that governments have attempted in the past, including wartime mobilisation, moonshots and industrial strategies, and particularly the writing of figures like Mariana Mazzucato.

The core claim of proponents of mission government was that the State has often played a decisive role in innovation and new technological developments. There are plenty of examples where that’s true. People typically cite the Apollo programme or initiatives like DARPA which catalysed the development of many products which underpin the success of Silicon Valley today.

The key question is whether these examples are generalisable, or whether they are the result of selection and survivorship bias. Like failed industrial strategies, failed missions are rarely given airtime, but we have plenty at home in the UK – the Concord programme and HS2 are both technological initiatives which could be characterised as missions, with significant public investment and focus over many years but nothing to show for those efforts today.

Historic examples of missions-led government have usually also had enormous geopolitical and security backing, and a high tolerance for failure and waste – neither are conditions which can easily be replicated for most missions the Government has chosen, and certainly not for all of them at once.

It’s not clear that mission-led government has an answer to these challenges. And if it did, it would still need a way to pay for the significant public investment which has backed previous missions. As the economy looks set for a period of higher interest rates, and our total debt hovers precariously around 100 per cent of GDP, it’s hard to see the financial markets being prepared for another big expansion of borrowing to fund more programmes. For the theory to work, missions need to find a way to either make cuts elsewhere more palatable, or make borrowing much more affordable – neither of which seem likely.

But even if you can generalise lessons about state leadership in technological innovation, and there were clear economic returns of significant public investment to do it, that wouldn’t solve this Government’s problem.

Because most of the missions the Government are pursuing today aren’t about technological innovation, nor are they as singular as ‘put a man on the moon’. In our research on missions, we drew a distinction between ‘technological innovation’ goals and ‘performance innovation’ goals. Mission-led government might have some answers on how to achieve the former kind, but there are good reasons those don’t translate to the kind of performance missions this Government are pursuing.

For starters, technological innovation missions usually involve building complex systems from scratch. The Manhattan Project, DARPA, even the Vaccine Taskforce and AI Security Institute – these are all institutions which were invented, and purposefully isolated from the wider objectives of government, to deliver specific missions. But fixing the NHS, tackling crime and better early-years help, these all involve re-engineering complex systems which already exist, and in doing so taking on the groups with interests in the status quo.

Failing to recognise this shows a kind of institutional romanticism at the heart of missions. It assumes highly capable bureaucracies, and downplays internal politics, inertia and risk-aversion. And it treats the State as a single big actor, rather than a federation of small groups, often working against each other.

In practice, government organisations optimise for process, not outcomes. They tend to punish failure much more than they reward success. Coordinating is incredibly complex across a government which spend c.50% of GDP and employs c.16% of the workforce. Delivering government policy through systems like these demands a different playbook to putting a man on a moon.

What comes next?

The Government’s plan to use missions as an operating model for the State was fundamentally flawed.

But while they were wrong in thinking missions were the answer, they were right that we need one.

Because governments can’t seem to govern any more. The levers of power are no longer attached to anything. The approaches to public management which created the bureaucratic states of the 20th century no longer seem to work for transforming them in the 21st.

There is no successor theory of public administration to New Public Management. Still the default operating model for the State, its teachings are deeply ingrained in the how the public sector works – from performance measurement to managerial autonomy, outsourcing, checks and balances, audits and inspections. It had its strengths, but it has not delivered on its promises of a more efficient and effective government, and decades later it is not fit for purpose.

Missions won’t replace it, nor are they the only contender. There are plenty of others – some with strengths but all with plenty of weaknesses. Deliverology, digital era governance, networked and relational states, liberated public services – all have had their moment, but none have stuck.

Some don’t think we need a different approach, just better application of the current one – but they are wrong. The Prime Minister’s ex-Director of Strategy was right when he recently called out the “Stakeholder State” for blocking change, but he was wrong that it’s easy to address – “a stiffened spine and renewed purpose” is as incomplete a plan of reforming the State as the missions were.

We need an approach to public management which is as transformative as current challenges demand. A new theory of statecraft, one which helps governments govern. Missions have failed to remake the State. What should replace them?

Our blog Re:Think exists to answer that question – developing on our central thesis of ‘Re:Imagining the State’.

Subscribe to be a part of it.

Good piece Joe, best I’ve read on the failure of the missions. However I do take issue with this: “Why did a Government with such a specific theory of change, and so much time in Opposition to prepare, abandon their plan within a year of taking power?”

Sadly it’s increasingly obvious that there actually was no such theory of change, nor proper preparation in opposition, nor an actual plan - not for missions or any part of its governing agenda.

Brilliant analysis of why the mission aproach collapsed under its own weight. The part about 'mission washing' to protect budgets really gets at how quickly ambitious frameworks get coopted by existing incentives. I saw something similar at a previous company where OKRs becamejust another layer of bureaucracy rather than forcing actual prioritization. The distinction between technological vs performance missions feels especially sharp when governmnent already struggles with basic service delivery.